You may be wondering why we make such a big deal about the drivers in the Frontier Studio Monitors being time aligned, and if you have memory of a certain cable company that became synonymous with snake oil calling their cables time aligned, you may be skeptical. Rest assured that this design feature is definitely not marketing nonsense and can make a very real difference in how you perceive your soundstage as well as the accuracy of your mixes.

What is a Time Aligned Studio Monitor?

Time alignment is when the sound of each driver (woofer, tweeter, etc.) in a system reaches your ears at the same time. The simplest and most consistent way of accomplishing time alignment is mechanically, which this article will focus on.

There are ways to accomplish this electronically with the crossover if the drivers are not mechanically aligned, (you can read about the Linkwitz-Riley crossover here for a deep dive), but as mentioned, this is outside the scope of this article and can often create different problems, which is why we chose to do it mechanically.

To mechanically time align a speaker or monitor, the acoustic centers (where the sound starts) of different drivers need to be on the same plane, so the air being pushed starts on the same plane. The practical effect of this is that sound from each driver reaches your ears at the same time. If you have a two way monitor, that means sound from the tweeter and woofer get to your ears at the same time, making the drivers aligned in time.

A lot of studio monitors and speakers are not time aligned simply because it's more expensive in development, parts and manufacturing. Most designs have the drivers mounted to the front baffle of the assembly, or the front panel of the speaker. Woofers, especially inexpensive ones, tend to be much bigger and physically deeper than the tweeters they’re paired with, with the motor of the woofer well behind the motor of the tweeters. Therefore, sound from the tweeters will reach your ears before the woofer, smearing the soundstage.

Why This Matters

Sound obviously moves very fast, and you may be wondering how an imperceptible delay in sound reaching your ears matters. Well, there’s really nothing imperceptible, it’s a matter of how brains interpret the sound hitting our ears, and while our brains don’t interpret this delay, as well, delay, it does interpret it as a phenomenon known as lobe tilt.

To dad joke this, speakers with lobe tilt are the drunk gunfighters of audio reproduction--they don't fire straight. If your monitors are upright and you’re in what you think is the sweet spot, the sweet spot may actually be your chest, and finding this sweet spot by aiming your speakers up is kind of a fool’s errand because of it being inconsistent from speaker to speaker and the cascading effects with acoustic treatment and everything else going on in your room. Imagine the mess if you place them on their side.

This tilt will also change based on your EQ settings while mixing, so you'll effectively be moving the tilt with your EQ.

As you’ve likely deduced, this is bad, and will affect how your soundstage will translate to other systems.

Different Methods of Time Alignment

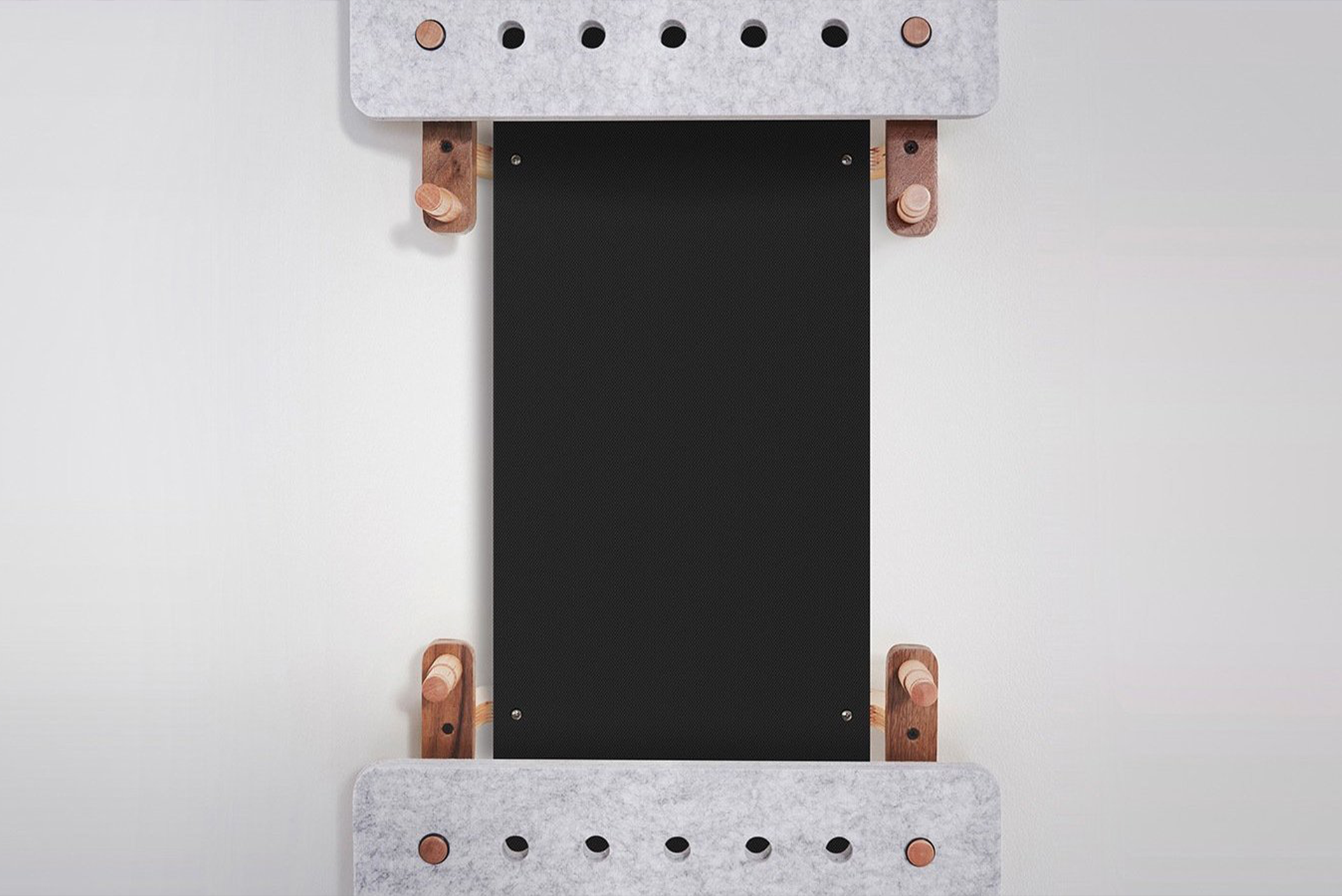

The method that we chose for Frontier while working with the brilliant Thomas Barefoot, was using a coaxial driver design where the tweeter literally sits in place of the woofer's dust cap. Another method is to use more shallow woofers or mid-range cones (in 3 way designs). Some designs put the tweeter on the back of a wave guide assembly, aligning the two drivers. There's also the tried and true method of an odd shaped cabinet with the tweeter sitting on a baffle above and behind the woofer.

You can also play tricks with physics by using an MTM, or D'Appolito design (I worked on the M-Audio EX-66 early in my career, falling kind of in love with this design), where the tweeter sits directly in between the woofers. This ‘contains’ the vertical high frequency dispersion and tends to make for a very narrow dispersion–less frequencies bouncing off the floor and ceiling. Directionality and soundstage are usually excellent with these designs. Many THX certified speakers are variations of this because part of the certification requires limited vertical dispersion for accurate sound design playback. The downside is that these are usually huge for near field monitors, and sound bad if placed on their side (Two woofers and a tweeter isn’t a true D’Appolito unless the tweeter is directly in between, so this side weirdness doesn’t apply to monitors like the Barefoot Micromain 26.)

Conclusions

Hopefully you’ve gathered that this is an important design feature worth the premium, and that whether accomplished with the crossover or mechanically, this is not a feature to be overlooked if serious about the quality of your studio monitors or playback system.